MNPS School Board member Amy Frogge highlights the importance of funding our public schools in her latest Facebook post:

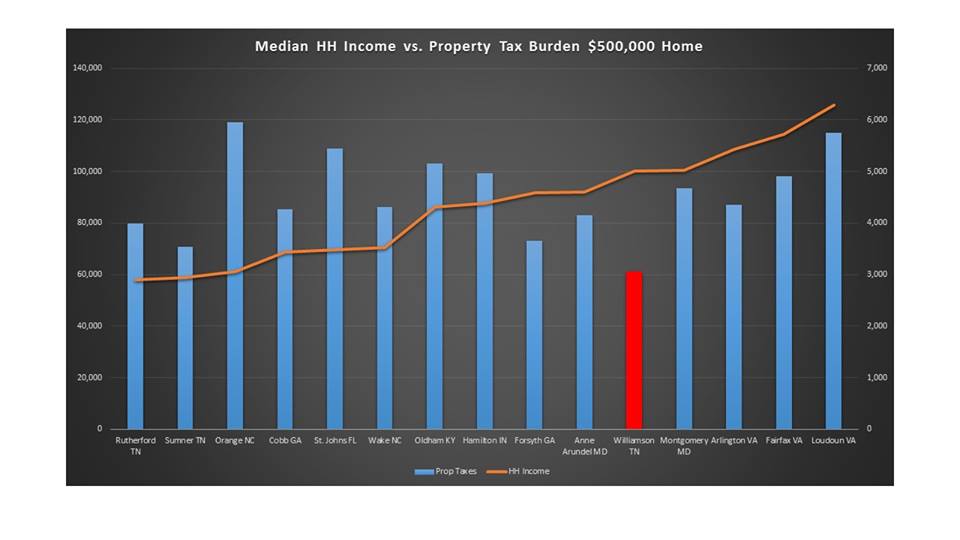

As the old saying goes: Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value. Despite all the hype from politicians (particularly this election year) that education is a top priority, Tennessee remains 36th in the nation on education funding, and Nashville ranks 54th out of 67 urban school systems in per-pupil funding (according to the Council of the Great City Schools). What better investment could our state make than providing ALL students with an excellent education? Yes, that money should be spent wisely, but adequate school funding REALLY makes a difference. Just ask any teacher (who- at one point or another- has probably spent her last $20 trying to buy supplies for her classroom).

I remember a conversation I had about school funding back in 2012, around the time I was first elected to the school board. Another elected official told me how awful local schools were, rolling her eyes at the thought of investing more money into our “failing” system. The irony of this conversation was that this person was spending approximately $25,000 per year to educate her own child at a prestigious private school- a school where, in addition to the high funding, students enter class already well equipped with every possible advantage. This article is for those who live in such a bubble.

Folks like this “won’t mention that there is research . . . showing that states that did provide more money to low-performing schools got better results — but never mind. . . .

And, apparently, people who don’t believe in a link between funding and student achievement won’t listen to teachers on the ground who can tell them otherwise.”

Frogge then links to this insightful article from the Washington Post about the impact of inadequate funding.

MORE on school funding in Tennessee>

What’s Missing is What Matters

For more on education politics and policy in Tennessee, follow @TNEdReport