In preparation for next year’s TNReady exams, it seems the Department of Education is already using some new math. While the General Assembly appropriated a $100 million increase in teacher compensation, an amount equivalent to a 4% raise, the Department is recommending that the State Board of Education adjust the state’s minimum salary schedule by only 2%.

Commissioner of Education Candice McQueen revealed the proposed recommendation in an email to Directors of Schools:

Directors,

Tennessee law requires the commissioner of education to present annually to the State Board of Education a state minimum salary schedule for the upcoming school year. Historically, the board has adopted the schedule at its regular July meeting after the conclusion of the legislative session and the adoption of the state budget. This year, in response to district communication and feedback, the board will consider the issue at a specially called meeting set for June 9.

The FY 16 state budget includes more than $100 million in improvements for teacher salaries and represents a four percent improvement to the salary component of the Basic Education Program (BEP). Because the BEP is a funding plan and not a spending plan, the $100 million represents a pool of resources from which each district will utilize its portion to meet its unique needs. The structural change in the state salary schedule in July 2013 recognized this inherent flexibility in the BEP by lessening the rigid and strict emphasis on years of experience and degrees and providing more opportunity for districts to design compensation plans based on a number of factors. At the same time, while recognizing the value, appeal and need for maximum flexibility, the state board has stressed the desire to improve teacher compensation, particularly minimum salaries, and Gov. Haslam has outlined his goal for Tennessee to be the fastest improving state in teacher compensation.

Considering this background information as well as feedback from districts and in an effort to provide districts with as much information as possible as early as possible, we want to inform you today that the department will propose increasing the base salary identified in the state minimum salary schedule from $30,876 to $31,500. This represents a two percent adjustment and will impact the other six cells on the state schedule accordingly. For example, the current minimum for a Bachelor’s Degree and 6-10 years of experience is the BASE SALARY + $3,190 or $34,066 (BASE of $30,876 + $3,190). The proposed minimum for the 2014-15 school year for this same cell will be $34,690, which represents the new recommended BASE SALARY of $31,500 + $3,190.

We believe this proposal strikes the right balance between maximum flexibility for school districts and the recognized need to improve minimum salaries in the state. For the large majority of districts, the proposal does not result in any mandatory impact as most local salary schedules already exceed the proposed minimums. For these districts, the salary funds must still be used for compensation but no mandatory adjustments to local schedules exist.

The current state salary schedule can be viewed here for a determination as to how your particular district may be impacted.

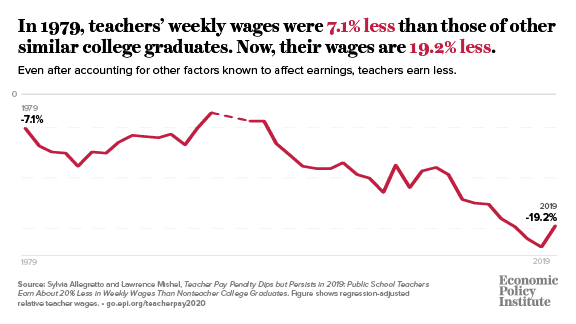

Two years ago, the state adopted a new salary schedule at the recommendation of then-Commissioner Kevin Huffman. This schedule gutted the previous 20 step schedule that rewarded teachers for their years of experience and acknowledged the work of earning advanced degrees. Historically, when the General Assembly appropriated funds for a raise, the Commissioner of Education recommended the state minimum salary schedule be adjusted by the percentage represented by the appropriation. So, if the General Assembly increased BEP salary appropriations by 2%, the State Board would raise the state minimum salary schedule by 2%.

This adjustment did not necessarily mean a 2% raise on teacher’s total compensation, because many local districts supplemented teacher salaries beyond the state required minimum. The 2% increase, then, was on the state portion of salaries. Some districts would add funds in some years to ensure their teachers got a full 2%, for example. And in other cases, they’d only get the increase on the state portion. Still, under the old pay scale, teacher salary increases roughly tracked the appropriation by the General Assembly.

Here’s a breakdown of average teacher salary increases compared with BEP increases in years prior to the new salary schedule:

FY BEP Salary Increase Actual Avg. Pay Increase

2011 1.6% 1.4%

2012 2.0% 2.0%

2013 2.5% 2.2%

These numbers indicate a trend of average teacher pay increases tracking the state’s BEP increase. In FY 2014, however, immediately after the state adopted a new pay scale designed to build in flexibility and promote merit pay, the General Assembly appropriated funds for a 1.5% salary increase and average teacher pay increased 0.5% — teachers saw 1/3 of the raise, on average, that was intended by the General Assembly.

Why did this happen?

First, nearly every district in the state hires more teachers than the BEP formula generates. This is because students don’t arrive in neatly packaged groups of 20 or 25, and because districts choose to enhance their curriculum with AP courses, foreign language, physical education, and other programs. These add-ons are not fully contemplated by the BEP. And, under the old pay scale, the local district was responsible for meeting the obligation of the pay raise for these teachers on their own. The BEP funds sent to the district only covered the BEP generated teachers. And then, only at 70% of the salary. Now, the district was free to use BEP salary funds to cover compensation expenses previously picked up by local funds.

Instead of addressing the underlying problem and either 1) increasing the base salary used to calculate BEP teacher salary funds or 2) increasing the state match from 70% to 75% or 3) doing both, the state decided to add local “flexibility.”

To be clear, increasing the base salary for BEP funds to the state average would cost $500 million and increasing the state BEP salary match would cost $150 million — neither is a cheap option.

But because every single system operates at a funding level beyond the BEP generated dollar amount, it seems clear that an improvement to the BEP is needed. Changing the BEP allocation to more accurately reflect the number of teachers systems need to operate would improve the financial position of districts, allowing them to direct salary increase monies to salaries.

An additional challenge can be found in Response to Intervention and Instruction — RTI2. While the state mandates that districts provide this enrichment service to students, the state provides no funds for RTI2’s implementation. Done well, RTI2 can have positive impacts on students and on the overall educational environment in a school. Because there is no state funding dedicated to RTI2, however, districts are using their new BEP funds for salary to hire specialists focused on this program.

Here’s the deal: 19 Tennessee school districts pay teachers at levels that mean they’ll have to raise teacher pay if the State Board makes the recommended 2% adjustment. To be clear, the minimum salary a first year teacher can make anywhere in Tennessee is currently $30,876. That will increase to $31,500 if the Board adopts McQueen’s recommendation. Because the 2% only applies to the base number and the other steps increase by a flat amount, a teacher with a bachelor’s degree and 11 or more years of experience will go from a mandated minimum of $37,461 to $38,085. That’s only 1.67%.

And let’s look at that again: The minimum mandated salary for a teacher in Tennessee with a bachelor’s degree and 11 or more years experience will now be $38,085.

That’s unacceptable.

Instead, policymakers should:

- Set the minimum salary for a first-year teacher at $40,000 and create a pay scale with significant raises at 5 years (first year a TN teacher is tenure eligible), 10 years, and 20 years along with reasonable step increases in between

- Fund the BEP salary component at 75%

- Adjust the BEP to more accurately account for the number of teachers a district needs

- Fully fund RTI2 including adding a BEP component for Intervention Specialists

- Adopt the BEP Review Committee’s recommendations on professional development and mentoring so teachers get the early support and ongoing growth they need

The policy reality is those districts at or near the state minimum are the poorest and least able to stretch beyond state funds. Following the proposed recommendation may well serve to exacerbate an already inequitable funding situation.

For more on education politics and policy in Tennessee, follow @TNEdReport