Tennessee State University Professor and Williamson County resident Ken Chilton offers his thoughts on the changing demographic landscape of Williamson County and the implications for politics and public education there.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city of Franklin was the eighth fastest growing small town in the United States between July 1, 2016 and July 1, 2017. That’s both exciting and scary. How will we pay for the schools? What about the congestion? How will we finance and manage all this growth? This is nothing new. Think of Levittown or the suburb you grew up in. Things change. Cities grow. Infrastructure gets built.

The growth of Franklin is dwarfed in number by the growth of Williamson County. The population of Williamson County grew by about 31,383 residents between 2010 and 2016. In 2016 alone, roughly 9,500 new residents moved to Williamson County from out-of-state or abroad.

Who are these new residents? Overall, 85.6 percent of Williamson County residents are classified as non-Hispanic white. In fact, between 2010 and 2016 the non-Hispanic white population grew by 24,000. Many of them have relocated to the Nashville region for employment and they chose Williamson County because of the public schools.

During that same time, the number classified as Asian grew from 4,432 to 7,752—a 75 percent increase in just 6 years. Likewise, the Hispanic population grew from 7,338 to 9,513. The African American population increased from 7,416 to 8,698, but its share of the population dropped from 4.3% in 2010 to 4.2% in 2016.

I believe Williamson County leaders and residents will figure out the growth puzzle. The bigger challenge is the ongoing demographic shifts and the future battles associated with rapid cultural change.

The Politics of Cultural Change

During the May primaries, some candidates appealed to traditional Williamson County values to garner votes. Such calls to nostalgia are often nothing more than dog whistles to a more racially homogeneous time. Regardless, there seems to be a growing resentment of newcomers. The new residents are accused of ruining the small town vibe, and presumably, bringing their non-Williamson County values.

Perhaps the opposition is not appealing to our basest instincts. Maybe it’s simply a matter of scale—we’ve reached a tipping point where the marginal costs of additional growth outweigh the marginal benefits of continued growth.

Invoking the “costs of growth” to rail against changes occurring in Williamson County is politically acceptable. However, do those who vocally oppose growth support policies typically associated with controlling growth?

Smarter growth means support for affordable housing. It means support for denser developments. It means support for impact fees. And, it means limiting the property rights of landowners who want to sell their properties to developers.

Most of the anti-government types in Williamson County resist all or most smart growth measures as big government interference in the private market.

Given this disconnect, I fear that some of the opposition to newcomers is rooted in “otherness.”

The changes are visibly evident. Go to Crockett Park on a Saturday morning and you will see plenty of racial diversity in YMCA sports leagues. My son’s YMCA tennis classes are racially diverse. A casual ride through Cool Springs reveals an increase in the number of Indian and other ethnic restaurants.

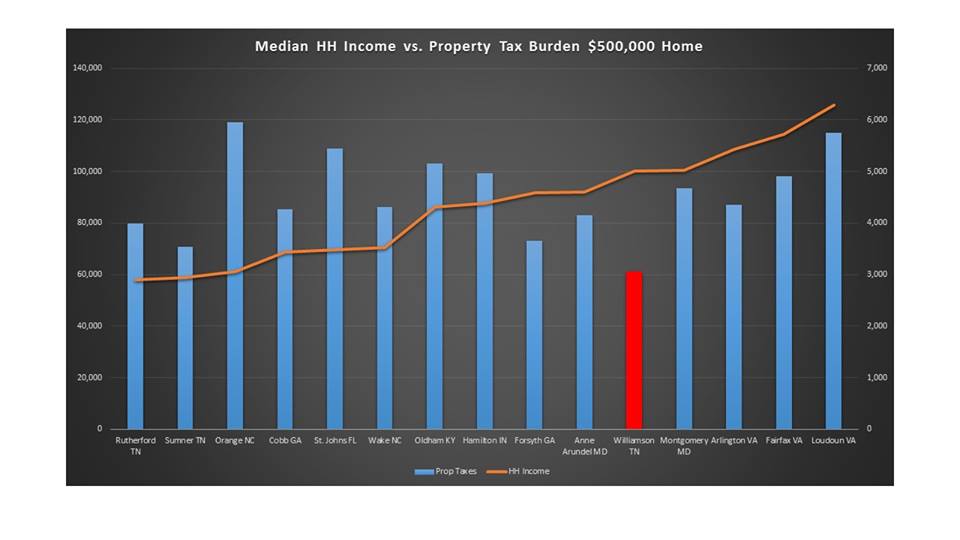

Many of the new residents are, first and foremost, parents seeking to maximize their children’s success. They might be Republicans, Democrats, or Independents in political affiliation, but their primary concern is maintaining and improving the quality of public schools. Some have moved here from high tax districts and they are fully supportive of efforts to increase public school revenues.

A quick glance at the age composition of Williamson County by racial group is instructive. Roughly 42.5% of the white population is aged 45 and older compared to 39.3% for African Americans, 21.1% for Hispanics, and 26.5% for Asians. The graying of Williamson County is most pronounced in the white community. In most cases, those over the age of 45 have less of a vested interest in the school system. Many no longer have children in the school system. Consequently, increasing property taxes to increase school revenues is a harder sell.

| Age | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian |

| <18 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 38.9 | 31.6 |

| 18-44 | 30.6 | 33.2 | 39.9 | 41.8 |

| 45-64 | 30 | 28.2 | 19.1 | 21.5 |

| 65+ | 12.5 | 11.1 | 2.0 | 5.1 |

Sharing Power & Resources

Williamson County must reconcile the concerns of an aging, mostly white, political elite that has called the shots in Williamson County for the past 30 years with the different preferences of new Williamson County residents. The May primary results are an example of how new voices are shaping local politics.

If opposition to growth is justified on the grounds that urban values are supplanting rural values, that’s xenophobia. No group has a monopoly on place. Neighborhoods transform. New residents bring fresh ideas to the public sphere. My property did not come with a deed restriction requiring me to support the political status quo.

Growth will continue to happen. You can either manage it or drown in it. You can either resent the newcomers or tear down walls and welcome them. The future is unwritten.

For more on education politics and policy in Tennessee, follow @TNEdReport

Got a story idea? Let me know at andy@tnedreport.com