The last few years of education debate and policymaking in Tennessee have seen a lot of negativity. You can name the fights off the top of your head: teachers’ unions and collective bargaining, vouchers, teacher evaluations, Great Hearts, charters vs. traditional public schools, K12, Inc., teacher pay, etc. There are more.

The last few years of education debate and policymaking in Tennessee have seen a lot of negativity. You can name the fights off the top of your head: teachers’ unions and collective bargaining, vouchers, teacher evaluations, Great Hearts, charters vs. traditional public schools, K12, Inc., teacher pay, etc. There are more.

I, for one, have been preaching, to everyone I can think to, that people on all “sides” of the debate have a lot more in common than we/you/they think.

I truly believe this.

What we need, then, is some common ground. Not faux common ground, couched as a talking point and then used to attack (“How can you not agree with X?”), but real, actual common ground.

Looking back at the pieces from my school board campaign last year, I came to re-read my “issues” section from my campaign website. I put a lot of thought and research into it at the time, and I think it still reads true. So, if you haven’t had a chance, here’s what I think the (beginnings of) a positive education agenda look like. It’s incomplete, for sure. But it’s a start. I’d love to hear what you think. P.S. I’ve cut out the “I’m going to be a great school board member” intro and skipped right to the issues.

************************************

Community-Supported Schools

No student should get a worse education because of their wealth or zip code. As research has shown, however, a student’s home life, socioeconomic status, and the health of their community have a strong correlation with that student’s ultimate academic success. Research has shown the increasing importance of communities and community support to schools. Professors Ellen Goldring, Lora Cohen-Vogel, Claire Smrekar, and Cynthia Taylor discussed this very issue in “Schooling Closer to Home: Desegregation Policy and Neighborhood Contexts,” a study specifically of Nashville schools and communities. (American Journal of Education, Vol. 112, No. 3 (May 2006), pp. 335-362). Cohen-Vogel, Goldring, and Smrekar also wrote an article entitled “The Influence of Local Conditions on Social Service Partnerships, Parent Involvement, and Community Engagement in Neighborhood Schools.” (American Journal of Education, Vol. 117, No. 1 (November 2010), pp. 51-78). Both of these articles shed light on this crucial issue, and support the idea of the importance of communities and community context in building strong schools and supporting student learning.

To a large extent, wealth and zip code determine student outcomes, but it doesn’t have to be this way. We can and must do everything in our power to support the educators and staff in our most at-risk schools, and provide them the support they need to overcome the achievement gaps our at-risk students suffer. Ultimately, this can only ever be an incomplete solution. Our schools need to become the centers of their communities again, and I will work to connect our parents, churches, neighborhood associations, community groups, and local residents to our schools. To achieve this goal, we need a board member involved with and connected to the community and community leaders so that we can tailor the resources and strategies needed in each school to fit the community those schools serve.

High Standards, Less Testing

High standards are excellent — there is no question that all children can learn, and that we do a disservice to them by lowering standards, or assuming they cannot think critically or master difficult concepts. Unfortunately, one of the most unintended, but very real consequences of the standards movement was the massive increase in testing of our students. These days, students spend up to several weeks out of their school year taking mandated tests. As well, because these tests are “high-stakes,” often determining funding and local control over schools and school districts, together with a focus of laws such as No Child Left Behind on reading and math skills, there has been a movement away from rich curriculum including science, art, music, physical education, and more. (See, for example, Richard Rothstein, “The Corruption of School Accountability,” (School Administrator, Vol. 65 No. 6 (June 2008) pp. 14-15). Good schools and good teachers constantly assess student progress, little by little, not just with a massive test at the end of every quarter or every year (if that even ends up being necessary). Good assessment shows where students are learning, and where teachers need to spend more time. Good assessment happens mostly in the background, and is supplemented by longer traditional tests like chapter tests and end-of-course tests.

As a school board member, I will push our district towards the latter concept of assessment, making use of technology such as Kickboard, so that, as a policy matter, we do not put massive, unwanted pressure on our schools, educators, students, and parents, with all the negative consequences that come with high-stakes testing, while still preserving the inherent good of standards-based learning and assessment. We can accomplish this by committing, as a district, to moving towards a collaborative model of teaching, where teachers are highly trained to use assessment and data in the classroom, and have mentors, master teachers, and coaches to help them, both in the use of that data, and in responding to the needs of their students.

High-Quality Teachers

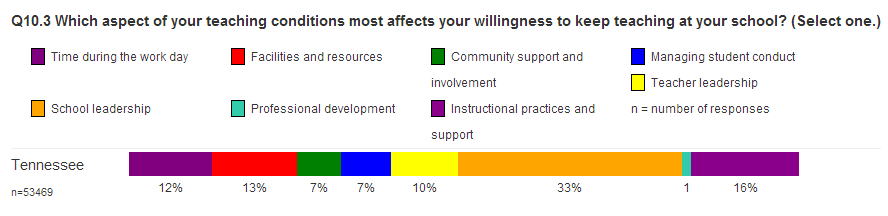

Teachers are the backbone of our public schools. As discussed above, though non-school factors play a major role in predicting student success, schools all over Nashville and Tennessee have shown that committed schools, with the right people and resources, can overcome a child’s background. Though it is not within the province of a school board member to recruit teachers to our system, we can put in place research-based policies that will lead to higher quality teachers who stay in our system. When asked, teachers overwhelmingly identify school leadership and school culture as reasons they do or do not stay at their school. For example, Tennessee’s own teacher survey, TELL Tennessee, shows the following results:

These results are typical — teachers want a strong school culture with a good principal, as well as support for good instruction. These are policy choices as to where we spend our dollars, and the latter option, “instructional practices and support” is a crucial issue addressed above with respect to assessment and support. As a school board member, I will support the district in finding school leaders who are quality instructional leaders, but who also reach out to and build connections with their teachers and the community around them.

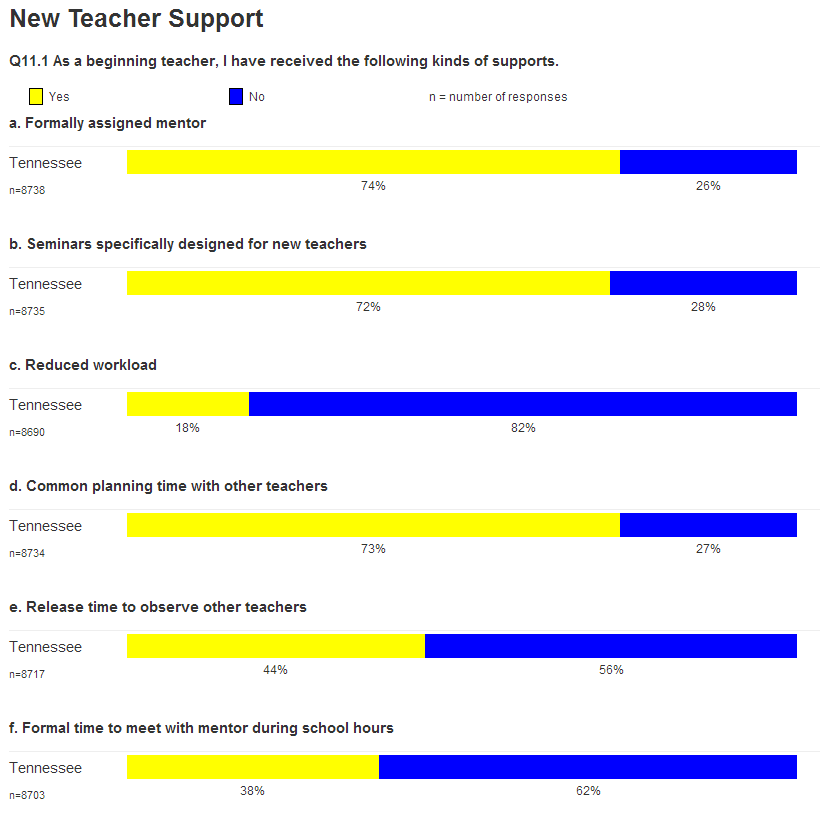

Teacher turnover is also a problem, especially in an urban district like Nashville. Paying teachers commensurate with our surrounding cities is a first step, and rewarding our excellent teachers must also be a priority. However, Nashville has a gaping hole when it comes to developing its newest teachers, so that we support and retain them. As I know personally, the first year of teaching is especially hard. Many teachers leave the profession during or after their first year. Again, it does not have to be this way. Nashville needs to make a multi-year induction, evaluation, and support program a cornerstone of our practice. The article, “What are the Effects of Induction and Mentoring on Beginning Teacher Turnover,” by Tom Smith and Richard Ingersoll, among others, shows that such programs can have an outstanding impact on developing and supporting excellent teachers, and retaining them in the district. (American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 41 No. 3 (September 2004) pp. 681-714). In fact, this is something beginning teachers are not being provided, though they want it (I certainly would have appreciated it during my first year teaching).

As you can see, though many teachers have a “formally assigned mentor,” a large majority of them do not have formal time to meet with that mentor during school hours, nor do they have time to observe other teachers, or have a reduced workload in order to learn how to be a good teacher. During my time at the Mayor’s office, working on the ASSET program, I pushed for such an induction and mentoring policy, and I will continue to do so on the Board.

As you can see, though many teachers have a “formally assigned mentor,” a large majority of them do not have formal time to meet with that mentor during school hours, nor do they have time to observe other teachers, or have a reduced workload in order to learn how to be a good teacher. During my time at the Mayor’s office, working on the ASSET program, I pushed for such an induction and mentoring policy, and I will continue to do so on the Board.

I believe deeply that we must support our teachers; we cannot fire our way to success. The labor pool does not exist to replace a massive amount of teachers in our system, and the resources we would expend would be wasted. There will always be some number of teachers who should not be teaching; I absolutely support removing such teachers. However, the vast majority of our teachers want to be good teachers. The vast majority are good people, committed to Nashville’s children. I will put in place policies on the Board to support those teachers, and give them the tools they need to be better.