Portfolios as a tool for teacher evaluation in Tennessee have received increased scrutiny in recent years. Kindergarten teachers told a legislative committee that implementation had been nothing short of a fiasco while the number of districts utilizing related-arts portfolios is dwindling.

Now, the Comptroller of the Treasury’s Office of Research and Education Accountability is out with a comprehensive study of the use of portfolios for teacher evaluation in Tennessee. Key findings include problems with validity and reliability as a measure of student growth as well as an increased time commitment for teachers and administrators. One policy suggestion is to move from attaching high-stakes (use in evaluation) to the portfolios and instead using some version of a portfolio as a tool for professional development. Below, I’ll post highlights from key areas of the report.

Platform Problems

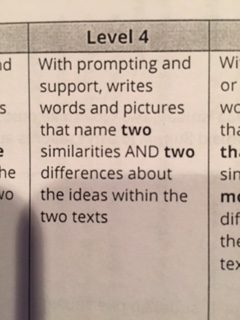

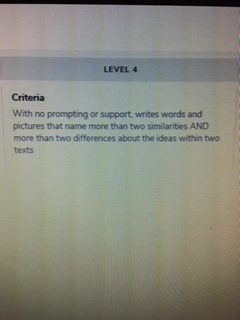

Educopia 2017-18

After the General Assembly began requiring all districts accepting VPK funds to adopt the pre-k/kindergarten portfolio model, the department sought a new platform vendor that could serve a significant increase in portfolio submissions and ensure consistency statewide in the submission process as well as the scoring process. For the 2017-18 school year, the department contracted with Educopia, a vendor that the state had already worked with to test a new scoring process.

Multiple issues with the Educopia platform and scoring process resulted in the department allowing teachers affected by uploading and scoring problems to have their portfolio scores removed from their overall evaluation (LOE) scores. These issues with Educopia contributed to the state choosing a different portfolio platform vendor, though TDOE had already planned to issue a request for proposal (RFP) for the following year’s (2018-19) portfolio platform in order to seek a platform that could align with a related TDOE system.

Portfolium 2018-current

In 2018-19, the state entered into a five-year contract with Portfolium. Like previous platforms, Portfolium also experienced capacity-related problems. On the last day to submit portfolios for the 2018-19 school year, Portfolium experienced a blackout and teachers were unable to access the platform. Additionally, at a meeting for peer reviewers to work on the first round of scoring, the heavy site activity overwhelmed the platform.

Program Costs

In the early years of the portfolio process, the Department of Education used the GLADiS Project platform and paid for the service through subscription fees. During the four-year period of 2013-14 through 2016-17, the department paid a total of $153,000 for the total 7,424 portfolios submitted during that period.B The department did not pay reviewers prior to 2017-2018; instead, districts recruited teachers to be reviewers and any compensation received by reviewers was determined at the local level.

For the 2017-18 school year, the state approved a sole source contract with Educopia, a vendor that the state had already worked with to test a new scoring process. The initial contract with Educopia was amended twice to increase the state’s financial liability, plus a subsequent short-term contract was approved. Increases to the state’s contract costs resulted from higher district and teacher participation than expected, as well as from additional vendor support required to address several problems with the platform’s implementation.

State payments to Educopia ultimately totaled $706,051 for work on the portfolio process for the 2017-18 school year, the same year that saw the number of teachers submitting portfolios rise from 2,170 to over 5,750.11 Adopting a new platform administered by a new vendor the same year as this large-scale increase in portfolio submissions likely increased the amount and complexity of the problems encountered and, by extension, the amount paid by the state. When the $677,000 in stipends paid to portfolio reviewers is added to the platform contract costs, the resulting total of $1.38 million makes 2017-18 the most expensive year for portfolio implementation to date.

The department released a request for proposal (RFP) for the 2018-19 school year, as it had planned, and awarded a contract to Portfolium, the only vendor other than Educopia that submitted a bid. The state signed a five-year, $2.1 million contract with Portfolium. In 2018-19, $216,496 was charged to the contract for the online platform, and $607, 282 was spent on portfolio review costs, primarily reviewer stipends. One additional cost of $26,100 was paid in 2018-19 for stipends for portfolio consultants, teachers, and other educators contracted to provide feedback on revisions made to scoring rubrics for clarity.

With 6,059 teachers submitting portfolios, the 2018-19 average state cost per portfolio was $140, not including compensation paid to three full-time department staff. This figure also does not capture local district costs. Some districts, for example, pay for classroom substitutes so that teachers have time to complete their portfolios during the school day.

Time Issues

Teachers report that the portfolio model takes time away from classroom practice and requires time spent after hours. State-required teacher assessments, whether based on standardized tests or on student growth portfolios, require time spent on preparation and administration.

A department survey of teachers using portfolios in 2017-18 found that 81 percent of all responding teachers (3,404) spent more than eight hours on portfolio preparation (e.g., uploading student work, adding explanatory comments, and completing self-scoring). Teachers using the world languages portfolio (24) reported spending the least amount of time on portfolio preparation, with 46 percent reporting they spent more than eight hours.

The portfolio process places demands on district administrators’ time as well, and these demands appear to be increasing based on changes in districts’ portfolio responsibilities outlined in state policy. As the statewide use of portfolio models expanded and the department understood the level of administrative support needed for successful portfolio implementation, the state’s requirements of districts grew.

Another concern of early grades teachers, in particular, relates more to the logistics of managing a classroom while also documenting the task performance of a selected student for a portfolio collection, such as recording audio of video of a student. For example, one pre-k supervisor indicated that portfolio collections were easier for pre-k teachers to put together than kindergarten teachers because pre-k teachers have a full-time teacher’s aide in their classrooms.

Summary

The above items reflect a portion of the OREA report on the use of student growth portfolios for teacher evaluations. The evidence indicates that these portfolios are expensive, incredibly time-consuming, and problematic to implement. The portfolios are also of questionable value when it comes to actually evaluating teachers. They MAY be of some use in professional development, if scaled-down and properly supported.

For more on education politics and policy in Tennessee, follow @TNEdReport

Your support — $5 or more today — makes publishing education news possible.